The Second World War has been described as ‘total war’ for the United Kingdom, because essentially the greater part of the population were engaged in it one way or another. A good many were in uniform, but there were also many thousands working in industries providing armaments, those industries working in support of them and industries supplying the essentials of life. For a good number of companies, total war began a long time before the first shot was fired, as the country began, albeit reluctantly, a process of re-armament.

In the chapter I explore the overall manufacturing position at the start of the war and then continue with radio.

Looking first at radio, further technical advances had made the mains-powered radio set easy to use, the extension of the national grid meant that, by the end of the thirties, two thirds of homes had mains electricity. More so, after lighting, the most frequently purchased electrical item was a radio. The industry was set for good times. So, in terms of places and manufacturers, Ruislip and Hayes would be home to employees of EMI. It was the new management of EMI who recruited a young and exceptional research department which powered the company to prominence; they provided the thinking behind the BBC’s structure for television broadcasting, some three years ahead of the USA. Their future partner, Thorn Industries, were based in Edmonton in North London. Philips’s and Mullard’s employees may have lived in Merton& Morden. Philips would dominate the European domestic electrical industry for some years after the war. Cambridge was home to Pye Radio who saw the huge potential of the Radiogram, bringing together broadcast and recording. Southend was home to Ecko, which had taken the radical step of using Bakelite for the bodies of their sets.3 GEC made radio receivers and telephone equipment in Coventry, but these were but part of their overall offering to the domestic market.

Turning to aviation, certainly Bexley and Chislehurst would be associated with Vickers Aviation; Harrow and Wembley with Hadley Page; Sutton and Merton perhaps also with Vickers. However all these areas were commutable and were places where building boomed in the thirties and so there is perhaps no need to identify each place with a large company. Southall had AEC and Slough all manner of the new industries. These were the industries where Britain, although perhaps not as leader, was still making a creative contribution to world manufacturing.

The coming of re-armament was a saviour for many areas. Cammell Laird at Birkenhead had an order book for 1932 of one solitary dredger, but in 1934 was awarded a contract to build the Ark Royal, 20,000 tons of aircraft carrier for £3 million. Between 1933 and 1938 the British government was to spend £1,200 million on military equipment much of which was on aircraft. In the period before rearmament was accepted as policy, the Navy had come first, but, with rearmament being taken seriously, the RAF and aircraft designers were determined that re-equipping should be with modern aircraft capable of competing with the best other countries had to offer. This was really where total war began, and very much with those well-known names long since gone from view.

I write much more about aircraft production, shadow factories and, not least, the jet

The contribution of the motor companies, which, in addition to wheeled and tracked vehicles and aircraft, included shells, tin hats and jerry cans, was massive. With the growth of this new industry aimed at a domestic market, it would form a huge reserve of industrial capacity once the domestic market closed and the demands of war grew. Much the same is true of the radio industry on the basis that many homes already had the sets with which they would listen to Churchill’s broadcasts, Music While you Work and much else, and so there was expert capacity to address the needs of the armed forces.

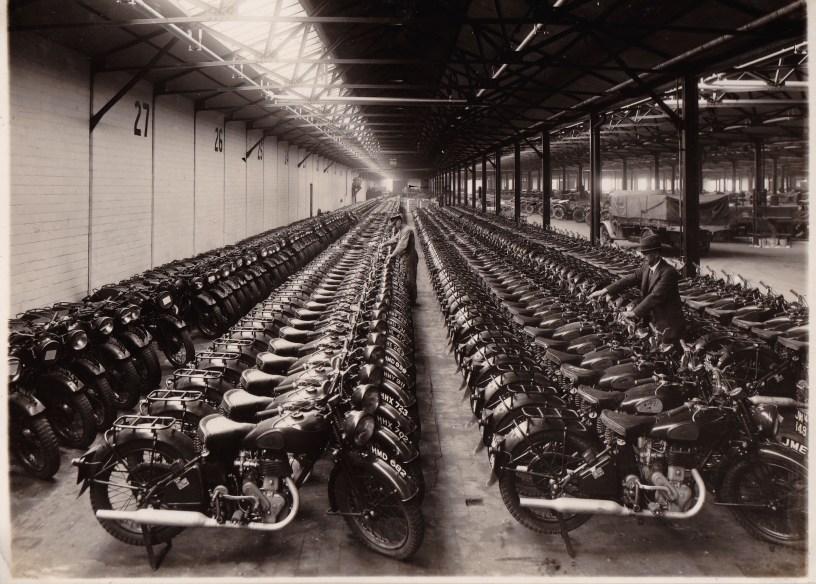

Looking first at the motor companies, an early port of call is the remarkable small book, Drive for Freedom, written by Charles Graves very soon after the end of the war. It was commissioned by the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders and was published by Hodder & Stoughton at two shillings. For me, the most remarkable feature is that it begins with my father, Major General Bill Williams, who created the army centre for mechanisation at Chilwell near Nottingham. I have written about my father in the book, Dunkirk to D Day, but Graves tells the particular story of Chilwell and the engagement with the motor companies. The key point is that Bill Williams saw as vital the expertise of the motor industry in advising how Chilwell should be set up; it was after all a massive motor dealerships and maintenance depot. Graves says, and my father’s archive confirms, that the industry responded to the approaches with great enthusiasm and generosity. There was, though, a second aspect. Bill saw that the RAOC, which would be responsible for the supply and maintenance of all army vehicles, would need amongst its officer ranks men with business experience. Interestingly, it was not the production men that he was seeking, but sales and distribution managers whose skills would be perfect and who would otherwise be redundant in war time Britain. Graves gives a number of five hundred senior motor industry men who joined the RAOC as temporary officers.

An industry, certainly in my mind closely related to motor vehicle, was toy making. British toy manufacturers had been encouraged during the First World War, and, following the peace, had reaped benefits both of wartime investment and the absence of German competition. The interwar years saw significant added capacity particularly by those who had established before 1914. G&J Lines had given way to the next generation three members of which formed Lines Brothers producing toys under the Tri-ang brand. They built the world’s most modern toy factory at a forty-seven acre site in Merton and by the early thirties had over one thousand employees. The Meccano factory in Liverpool doubled in size and Hornby, which were already producing O gauge clockwork trains, took advantage of the growing number of homes with electric power to bring out it famous OO electric trains. Hornby began manufacture of their Dinky vehicles in 1934. In London, Britains opened two more factories and Chad Valley acquired an additional twenty acre site. Most of the toys wanted by British children were now being produced at home and at an acceptable price and quality. The toy manufacturers were supplying an hungry market in the 1930s and in the early months of the war, readily available were box sets of soldiers from Britains and Dinky models of army vehicles. With the end of the phoney war, toy manufacturers rolled up their sleeves for the war effort. Britains and Mettoy, who in the fifties would be known for Corgi model vehicles, switched to munition manufacture, Lines Brothers manufactured machine guns, parts of gliders and ammunition magazines and Bassett-Lowke made training models for the forces including Mulberry Harbours.

I write of shipbuilding, Code Breaking and the Royal Ordnance Factories.

Of equal significance was the invention by ICI chemists of Perspex which was used in the windscreens of aircraft. This had come earlier in conjunction with the development of the Spitfire which incorporated Perspex in its cockpit from 1936.

In 1937 the complete patent specifications for polythene were filed and each of the Plastics, Dyestuff and Alkali Divisions pursued research into its possible uses. Carol Kennedy tells the full and fascinating story including that it was Metropolitan Vickers which carried out research into its electrical properties. However, it was John Dean of the specialist cable makers, Telegraph Construction and Maintenance who established the value of polythene as an insulator. From this the developers of polythene discovered that it was perfect insulation, preferable to both rubber and gutta-percha, for the many miles of cable required by the newly invented radar defence system and was put into production just in time for the Battle of Britain.

ICI was far from alone in the British chemical industry. British Celanese at Derby manufactured parachutes and underclothing. By the end of the war, they employed 20,000 people. In conjunction with Courtaulds, ICI formed British Nylon Spinners to exploit the Du Pont patent of Nylon for the manufacture of parachutes.

You can read more in How Britain Shaped the Manufacturing World. Sadly, my book on the mechanisation of the army in WW2 is now out of print but you can find a good deal on my blog.