This post seeks to give a flavour of an important chapter in the story of British manufacturing through a few short extracts from an otherwise long chapter.

In March 1896, Lawson set up the Daimler Company with fellow director, Gottlieb Daimler, and bought the Daimler patents from The Daimler Motor Syndicate Limited; Frederick Simms became a director as consulting engineer. The new company took a lease on a fourteen acre site in Drapers Field, Coventry and began production. The site had belonged to Coventry Cotton Mills, and Lawson renamed it Motor Mills. It was the first motor car factory in Britain and would house, in addition to Daimler, the other motor and motor related companies Lawson owned. By 1897, it was employing 223 people and exhibited at the Stanley Cycle Show.

Frederick Lanchester was probably the opposite of Harry Lawson. He was born in 1868, son of an architect, and had a formal mathematical and scientific education before moving to Finsbury where he learned workshop practice. We know this from a detailed and admiring obituary written in 1946 by Harry Ricardo, himself a celebrated motor engineer who, amongst much else, designed the engine which succeeded the 105 hp. Daimler engine that had powered the first tanks. The obituary appeared in the journal of the Royal Society. Ricardo explains how the early ‘horseless carriages’ from the continent were just that, carriages with internal combustion engines rather than horses. They were noisy, vibrated uncomfortably and had suspension unsuited to the faster vehicle. Lanchester had begun his career in 1895 in Birmingham working on gas engines, and there began to build his first car, the first all-British four-wheeled vehicle. He formed the Lanchester Engine Company and produced two more models. Ricardo wrote how he had driven one of these early models and could therefore vouch for their quietness, lack of vibration and smooth ride. He puts it that Lanchester had the remarkable combination of mathematical, scientific and engineering skills. Lanchester wrote two seminal works on aircraft and many learned papers. The third model he made went on to sell well and was widely respected for the quality of design and manufacture. Ricardo explains that Lanchester carried a heavy burden, since, not only was he managing director, he was designer and works manager. He puts flesh on this by adding that every part, except for tyres, had to be made, and, since the technology was new, even experienced mechanics had to be taught new skills. Probably because of all of this, the company was not a commercial success and a receiver was appointed. In 1905, Lanchester started again with the Lanchester Motor Co Limited and production and indeed development continued. In 1909, Frederick Lanchester fell out with his fellow directors and become a consultant, and, at the same time, became a consultant to the Daimler Company.

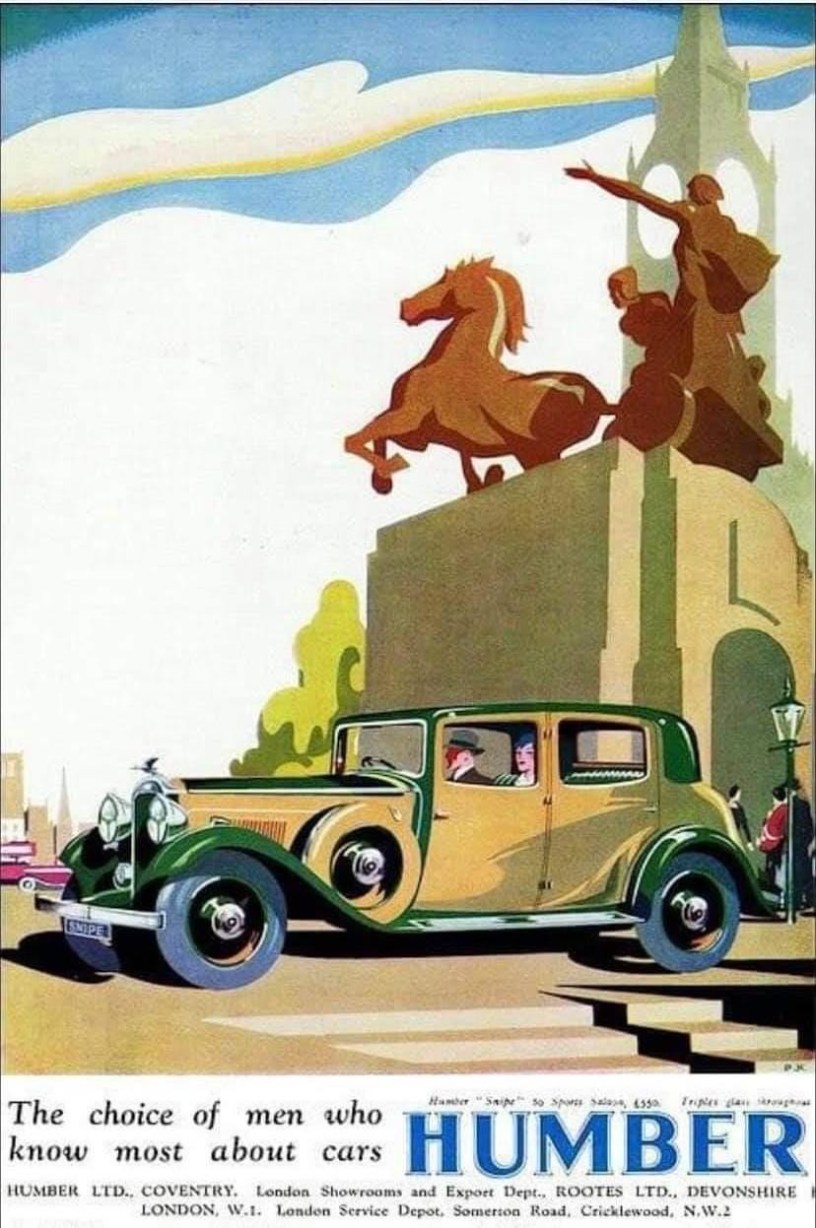

William Hillman had also been producing bicycles in Coventry for some years, but in 1907 he set up the Hillman Coatalen Company, when Louis Coatalen left Humber. Coatalen was clearly a man uncomfortable in the same place for too long, and, in 1909, the partnership with Hillman was dissolved and he went to join Sunbeam and its founder John Marsden. Sunbeam was building cars in Wolverhampton under works manager Sydney Guy who would go on to found Guy Motors. He had previously worked at Vickers Sons and Maxim, at General Electric Company and at Humber. Guy thus links the world of heavy engineering, motor vehicles and electricity. An early Sunbeam was reputedly the first car ever to be driven a more than 200 miles per hour. The Hillman Company continued to prosper, itself winning a number of awards. It would join, Humber, Sunbeam and Singer which made up the passenger vehicle side of the Rootes Group. [My dad was export director of Rootes in the fifties]

We can now move west to Oxford where, in 1893, William Morris set out on his career, first repairing bicycles. I know rather more about him than the others, probably because of his later fame as Lord Nuffield. One by-product of this is an engaging biography of him written in 1955 by P.W.S. Andrews and Elizabeth Brunner which I think my father bought when it was first published. In this, they offer revealing anecdotes about the man and his business, but also valuable reflection on the business of making motor cars from very nearly the start.

Motor bikes, however, were not where Morris saw the future, and so he set about designing a motor car. He had been running a business both repairing and hiring cars, and this had taught him a massive amount about what worked and what didn’t. His reputation had also attracted other manufacturers to appoint him as their sales agent in Oxford, and he was selling cars for well-known motor car makers such as Arrol-Johnson, Belsize, Humber, Hupmobile, Singer, Standard and Wolseley and motor bikes for Douglas, Enfield, Sunbeam and Triumph.

What of other manufacturers? What, for example, of Rolls-Royce? Henry Royce had run an electrical and mechanical business since 1884, and in 1904 met Charles Rolls, an old Etonian car dealer. Royce had made a car powered by his two-cylinder engine, which greatly impressed Rolls. The two agreed that four models would be made under the Rolls-Royce brand and that Rolls would have the exclusive right to sell them. The car was revealed at the Paris Motor Show of 1904. The two men needed to find a factory in which to make them. Derby offered them cheap electricity, and so they selected the site at Sinfin Lane where a factory was built to Royce’s design. I write in the next chapter of the revolution that electricity brought about.

I go on to write about motor components, so Dunlop and Lucas, but then powered flight pre WW1 and the move to diesel. As to powered flight….

The Sopwith Aviation Company, perhaps the most iconic from the First World War, was founded at Kingston-Upon-Thames in 1912, and its Sopwith Bat Boat No 1 was the first flying boat to be built in Britain. Another pioneer, Noel Pemberton-Billing, showed his Supermarine PB.1 at Olympia in March 1914, but it never entered production. The name Supermarine, when associated with its offspring the Spitfire, would become one of the most loved in aviation in the Second World War.

You can read much more in my book How Britain Shaped the Manufacturing World.