Armstrong and Krupp and the French arms manufacturer Schneider came to be known as ‘Europe’s deadly triumvirate’…’over the next eighty years they were to be celebrated first as shields of national honour and later, after their slaughtering machines were hopelessly out of control, as merchants of death.’

William Manchester – the biographer of Krupp

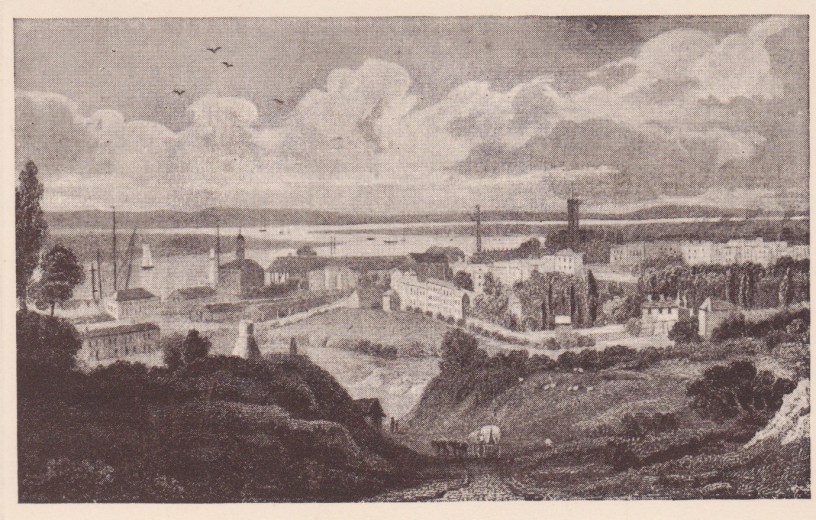

In 1805, the Ordnance Factories at Woolwich, which supplied army and navy with cannon, had been re-designated The Royal Arsenal, and began also supplying muskets but ‘the work was confined to rough stocking and setting up barrels bought from private firms in Birmingham’. In 1807, a factory was acquired at Lewisham to provide barrels and locks, which was moved four years later to Enfield’ At about the same time, the barracks at Weedon were taken over for the storage and inspection by armourer sergeants of Birmingham produced muskets. The iron works at Dorlais in South Wales, run by John Guest, supplied cannon balls to the army. A brief glance towards the Royal Navy brings in the name of Marc Isambard Brunel and his contract in 1803 to manufacture pulley blocks for the Royal Navy. Significantly in this story, this was one of the very earliest examples of mass production with individual workers performing the same single task only in a multitask process on a standardised product. Marc Isambard Brunel was the father of Isambard Kingdom Brunel and, like so many who made England their place of work, was not of British descent, but French.

The Arsenal was under the control of the Board of Ordnance, of which the Duke of Wellington was Master General from 1818 to 1827. A gunpowder factory had been set up at Waltham Abbey in 1787, whilst most armaments were then stored at the Tower of London. The making of muskets had originated in the narrow streets surrounding the Tower of London. The iron had come from the smelters in the Weald where there had been accessible quantities of iron ore and plentiful wood for charcoal. The shortage of wood in Elizabethan times had largely killed off the Weald as a source of iron, and supplies were had from elsewhere. Birmingham, originally had taken its iron from smelters in the Forest of Dean, but coal was readily available in the black country as an alternative means of smelting, and so the manufacture of guns naturally gravitated there.

In the chapter I tell of the modernisation of the Arsenal. Britain though was predominantly a naval power and so it is to the steel companies and shipbuilders I turn for much of the chapter’s contents.

Armstrong had combined with the Mitchell shipyard on the Tyne in in 1883 and, building on the success of Armstrong’s rifled cannon, the Elswick works was fast becoming an ‘arsenal complete in itself’. Heald tells that, in 1896, Armstrong was becoming concerned that Vickers, fast catching up with both themselves and Krupp, would present serious competition to Elswick particularly in the field of armour plate.

Vickers was still at heart a steel company, but, towards the end of the nineties, the directors had made the decision to shift their focus to armaments. The Vickers family were already involved with inventors, Maxim and Nordenfelt, developing the machine gun and submarine; they had already manufactured guns and armour plate for naval ships. In 1897, they took the plunge and purchased the Barrow Naval Armaments Co shipyard at Barrow in Furness. The Barrow yard had been founded by the Dukes of Devonshire, one of a number of examples of landed wealth becoming involved in manufacturing. With the purchase of the yard by Vickers, the Duke became one of its major shareholders. The completion of the railway from Carlisle to Furness had opened up this hitherto backwater which became a hive of industry. Vickers also bought Maxim-Nordenfelt and soon secured major naval orders for the Barrow yard.

Whitworth, in Manchester, had been producing quantities of armour plate at their Openshaw works, and were well regarded by the Admiralty. Armstrong feared that Vickers would buy them, and so he made his own bid which was successfully concluded in 1897, when the company became Armstrong Whitworth. Armstrong, once combined with Whitworth, ranked seventh of the shipyards in order of size of production. Another combination, Cammell Laird, at Birkenhead came tenth in the table with Vickers at Barrow eleventh. One of the key developments of these two decades was this marriage of shipbuilding and armaments. In this regard, John Brown & Co on the Clyde, with its Sheffield armour plating production, rank fourteenth out of twenty.

These are the core names that would provide the muscle in WW1 and I write of their role in army supply on my book Ordnance.

Other developments I write of in the chapter are growing use of telephone and telegraph and the early use of wireless. Of no less importance was the invention of the tin can.

You can read much more in How Britain Shaped the Manufacturing World.