Britain’s second city has been described as a city of a thousand trades and so quite different to Sheffield with its focus on steel, Manchester on cotton and Leeds on wool. Having said this, in the nineteenth century its production of brass and objects made from brass made it a world leader, with Birmingham parts present on steam trains the world over to say nothing of door furniture and the very many other items made from the metal. It has always been an industrious city but with a core of small and medium size enterprises, a great many working with metal.

In this post I explore Birmingham’s manufacturing history. Looking back to the origins and early development of the city I offer here an essay I wrote for my BA Humanities, it was titled: Describe the development of industry in one town and explain its impact on the town growth and environment. This comes further down the post. The image is of the Chamberlain clock tower in the Jewellery Quarter which to my mind speaks of Birmingham’s pride but also its intellectual life; Birmingham was the city of Darwin, Chamberlain and Priestley.

Looking at the last couple of centuries, large scale manufacturing was first focused on the iconic Soho Works of Boulton & Watt. I began the story in Glasgow where James Watt was in business as a mathematical instrument maker but his work in developing a steam engine better than that of Newcomen had run out of money. Mathew Boulton stepped in to ensure the work continued. Boulton was businessman and his Soho works of which I wrote in my essay (see below) was a modern building providing workspace for a great many skilled craftsmen making all manner of metal goods. Boulton thus had the skills Watt desperately needed to bring into reality Watt’s theories and drawings. He had some money, and the means to raise more, and a relationship with an iron master named Wilkinson skilled at fine castings. Samuel Smiles in his contemporary account of the Lives of Boulton and Watt, tells of the many trials and tribulations encountered in bringing a fully functioning steam engine to commercial success. The first objective was to produce an engine capable of pumping was out of deep mines but also one that used a good deal less coal than Newcomen’s. The intended customers were Cornish, mining for copper and tin. Smiles tells of Watt’s time in Cornwall, the scenes of mining waste everywhere and the hostility of unbelieving Cornish to Watt and his promises. He did succeed but only under severe financial constraints given the capital demands of the business. These demands derived from the cost of enlarging the Soho premises but also the terms of business whereby mine owners would pay a roylaty based on the fuel savings achieved. Nonetheless, Boulton raised finance and won orders from Britain but also France and Holland. Boulton also invested in some of the Cornish mines to secure his income. There were other obstacles to success. Even though Boulton employed skilled craftsmen, it was challenging to get them to erect the steam engines with sufficient care. Drink played its part as did, in Cornwall, the often physical opposition of the miners.

William Murdock was a shining exception and over the years he became an increasingly important part of the business. He was a man very much in Watt’s mould and was forever finding better ways of making but inventing afresh. Smiles tells how he found a way of extracting gas from coal and then lighting that gas to illuminate a room.

Watt went on to invent a steam engine powering a rotary motion but all the time was weighed down with cash flow worries, patent challenges and rumours of even better engines being developed elsewhere. In time these worries weighed less heavily.

Matthew Boulton was for ever keen to explore new uses for the steam engine. The city’s businesses were the biggest producer of brass objects using the product of Cornish mining. The problem wa that one of the objects so produced was counterfeit coinage. It seems that the Royal Mint couldn’t meet the demand for coin generated by the increase in economic activity. In stepped the less scrupulous with their home produced coins. Counterfeiting of gold and silver was met with fierce penalties and in time reduced. No so, copper. Boulton invented a way of pressing coins to a very tollarance and producing them in large quantities. The Royal Mint was not impressed and so he directed his efforts towards other countries who welcomed his product. He went from coins to commemorated coins and medals which were equally welcome. Some ten years after building his first minting machine, the Royal mint at last took his coppers. Business thrived.

Matthew Boulton and James Watt were enquiring individuals and they would meet with like minded men in a group known as the Lunar Society, so named because it would meet on the Sunday evening closest to the full moon to ease the journey home for those not resident in Birmingham such as Josiah Wedgwood and Dr Darwin (the physician father of Charles). Another significant member was Dr Priestley whose interest was in chemistry, particularly gases.

Joseph Hudson made whistles. His were adopted by the Metropolitan Police and his Acme whistle is still used by referees.

Elsewhere in Birmingham, Elkingtons invented electroplating of silver on nickel which boosted Birmingham’s trade in domestic luxury items. Picking up on its intellectual life, companies in the city produced more steel pens than any other such manufacturer in the world and exported far and wide. Alongside the pen was paper and printing in which the city excelled. Alongside books was of course chocolate and the Cadbury family began their long relationship with the city by the canal at Bourneville. Brass also had its darker uses and Birmingham was a major producer of guns with the Birmingham Small Arms Company. With the growing demand for trains, the Birmingham Railway Carriage and Wagon Company manufactured in Smethwick. Joseph Wright’s Metropolitan Railway Carriage and Wagon company manufactured at Washwood Heath. This company would become Metro Cammell in 1929 when Vickers and Cammell brought together their railway manufacturing interests. It was bought by GEC Alsthom in 1989.

In 1834, in Birmingham, John Nettlefold had opened a woodscrew mill. And in 1856, just down the road, Arthur Keen had founded the Patent Nut & Bolt Company (PNB) with his American partner, Francis Watkins, and which had become a major manufacturer of fasteners. In 1900 it was Arthur Keen who bought first Guest’s Dowlais Iron and Steel works and then Nettlefold’s business, creating Guest, Keen and Nettlefold or GSK as it later became. In the interwar years, Nettlefolds proved to be the profitable part of GKN largely as a result of their efforts in marketing their wood screws. They enjoyed a dominant market position and secured it by buying competitors. They took a licence to manufacture the revolutionary ‘Phillips’ screw and in the Second World War turned their attention to adopting up to date production methods. The nut and bolt business based on PNB had benefitted from little investment. When the time came to modernise, the directors decided to buy better equipped competitors rather than spend money on outmoded and decaying buildings.

GKN moved into automotive transmission equipment by buying Birfield which included Hardy Spicer and acquiring a stake in the European Uni-Cardan which opened up continental markets. Famously Hardy Spicer had developed the constant velocity joint which was fitted in Minis and now many other vehicles world-wide. At the start of the eighties GKN employed 104,000 people worldwide when recession struck and the workforce was halved. GKN is now owned by Melrose plc which demerged the Automotive business as Dowlais Group plc leaving it as primarily an Aerospace business based in Bristol.

Joseph Lucas set up business in the distribution of oil lamps, but, with the coming of the bicycle, saw the opportunities available to manufacturers. He was joined by his son Harry and, in the late 1870s, they set up in partnership manufacturing bicycle lamps. From this grew one of Birmingham’s great companies of which I write more in this link.

Reynolds Tube Co would become part of Tube Investments which was formed in 1919 and drew together four of the city’s steel tube makers. Over the years more tube makers were added. The company participated in steel making for example in collaboration with Stewarts and Lloyds at Corby. (Lloyd & Lloyd were a steel company which combined with Stewart’s of Glasgow to form the Corby Steel Works). A logical extension from steel tubes were the bicycles they made. In 1946 Tube Investments bought the Hercules Cycle Company of Birmingham, which had been founded in 1910 and focussed on streamlined production methods which gave it a cost advantage. Later TI bought essentially all the British bicycle companies culminating in Raleigh of Nottingham where production was concentrated. Another strand to TI’s bow was machine tools and the company bought most of the famous British tool makers including the rump of the failed Alfred Herbert. Heating boilers came into the fold with Parkray and Glowworm of Belper. A more significant diversification came with the purchase of the Dowty Group and this culminated in TI joining in Smiths Industries. Simplex Conduits of Birmingham merged with Credenda Conduit Co of Oldbury both owned by Tube Investment to form Simplex Electric Co which began to manufacture Creda domestic cooking appliances in addition to lighting equipment and conduits

Chance Brothers made the glass for the Great Exhibition. John Nettlefold’s woodscrew mill would become part of GKN which would have significant presence in the city. Bird’s custard was made in Birmingham. Along with Coventry and Wolverhampton, Birmingham engineers made bicycles. I write of these magnificent companies in How Britain Shaped the Manufacturing World and Vehicles to Vaccines.

Albright & Wilson set up in Oldbury in 1850 producing bantling phosphorus and chlorate of potash on land they had purchased from Chance Brothers. The works continued to manufacture a range of chemicals and was probably best known for phosphorus, phosphates and related chemicals. It was also in several overseas territories and supplied many industries, such as detergents, toiletries, paper, metal finishing, food agrochemicals and textiles. Albright & Wilson also adopted a new process of acid production from anhydrite using reserves at Whitehaven.

The First World War laid down a major challenge for Birmingham as it did for other cities including Coventry. British Commander in Chief Sir John French is quoted as suggesting that the war was a struggle between Krupp and Birmingham. BSA was producing Lee-Enfield rifles, Lewis guns and motor bikes; by 1918 it employed 14,000 people. Naturally alongside engineering, machine tools companies were fully occupied. BSA already manufactured small tools but expanded to make the larger machinery they needed but that was also need in the national arms factories. There was a National Shell Filling Factory at Washwood Heath and Mills Munition Factory produced many thousands of Mills bombs. Kynoch’s at Witton produced high explosive and rifle ammunition. They later joined 29 other companies in Nobel Industries Limited. Cadbury provided much needed chocolate.

Harry Lucas was keen to provide motor companies with what they needed for the war effort. A major problem was that the War Office had specified Bosch Magnetos for their vehicles. The components industry pre-war had been content with this, and the ability of British companies to supply magnetos was strictly limited. One company in particular, Thomson Bennett, rose to the challenged. Harry Lucas pounced when, in 1914, the opportunity arose to purchase it. This was going to prove of massive value to Lucas in the years to come, not least in the person of Peter Bennett. During the war, Lucas grew to some 4,000 employees, 1,200 of whom were making magnetos.

Parkinson made gas stoves and later became part of Parkinson and Cowan.

The interwar years were challenging, but less so for Birmingham than for its fellow cities geared more to shipbuilding and steel.

Birmingham developed into a significant player in the motor industry. The Land Rover is a child of Birmingham with Rover’s founders, the Wilkes Brothers, setting up production in Solihull when their Coventry factory was destroyed by enemy bombing in the Second World War. The Solihull former shadow factory also took over the manufacture of Rover’s saloon cars. From 1970 it focuses on the highly successful Land Rover and Range Rover.

The famous Fort Dunlop speaks of the rubber and tyre industry. It was built during the First World War and the company had also bought rubber plantations in Malaya and cotton mills in Rochdale. In the wake of the war, Dunlop suffered from the rashness of its management but recovered with the appointment of Eric Geddes and George Beharrell who had worked closely with Lloyd George in arming the nation in the war.

Lucas had their HQ at Great King Street, but spread throughout the city with automotives, brakes at Tyseley, aerospace at Marshall Lake Road and Marston Green and at Great Hampton Street. Lucas also manufactured in the Jewellery Quarter benefitting from the fine metal working skills. In the interwar years, Lucas were growing their business in a number of very focused ways. They accepted offers by the smaller component manufacturers to buy their businesses, and then, a little later, agreed to buy their two larger competitors, Rotax and CAV when the latter experienced harsh trading conditions in the mid 1920s.

In the late 1920s, the motor companies came round to the idea of safety glass and Triplex grew out of its premises in Willesden and moved to Birmingham with financial backing from Guest, Keen and Nettlefold. In 1927, St Helen’s glassmaker Pilkington developed a way of making thin glass and they entered into a joint venture with Triplex to exploit this.

W.T. Avery, the weighing machine company which later became part of GEC, was run in 1919 by Sir George Vyle. Appointed as Vyle’s financial adviser was the WB Peat & Co trained Percy Mills, a Stockton man who parents had made confectionery. Mills rose in the business eventually to become managing director until he retired in 1955. He played a major role in wartime supply first as Deputy Director of Ordnance Factories and then as Controller-General of Machine Tools. He went on to hold a number of senior public appointments. He was created Viscount Mills and died in 1968.

Percy Mills’s father in law was a Dublin engineer George Conaty who joined the Birmingham and Midlands Tramsways Company which ran services between Birmingham, Smethwick, Oldbury, Tipton, Dudley, Sedgley and Crosley using both steam and electric powered trams. He went on to be manager of the City of Birmingham Tramways Company where he contributed his technical skills in patenting a new system for tramcar bogies. Conaty had been apprenticed to Thomas Green and Son in Leeds who built locomotive and tramway engines. Conaty may also have been inspired by the Aberford Railway on which he travelled daily and which had transported coal to the depot on the Great North Road. Trams were appearing across the country and Birmingham’s Midland Railway Carriage & Wagon Company Limited were said to have built one of the first electric trams with Elwell-Parker Limited of Wolverhampton who manufactured and fitted the motor and all of the electrical equipment. Other manufacturers included English Electric of Preston, Brush of Loughborough and Metro Cammell in Oldbury which had been set up by Jospeh Wright in 1846 and later merged with other railway manufacturers and was in 1928 owned jointly by Vickers and Cammell Laird. I write of the consolidation of the railway manufacturers in How Britain Shaped the Manufacturing World.

Back in Birmingham, in 1902, GEC had put up a purpose built factory at Witton near Birmingham in which they manufactured a large range of electrical machines and appliances. GEC made large electric motors, generators and switchgear. In 1920 the company produced a collage of images of its many factories. These included the Conduit Works; the Carbon Works; the Switchgear Works; the Engineering Works, all at Witton and the Meter Works, elsewhere in Birmingham and also the Art Metal Works. In 1930 they were making Magnet industrial and domestic appliances. West Bromwich was home to GEC Installation Equipmen. In 1962, GEC employed 11,000 people in Witton over 60 acres making rotating plant from fractional horsepower motors to the largest generators, switch and control gear transformers of all sizes and rectifiers.

Herbert Austin set up the company bearing his name in Longbridge to the south of the city and the company on which he cut his teeth, Wolseley, both built vehicles for the forces in the First World War. It wasn’t just vehicles, during the war the Austin Motor Company produced 8 million shells and 650 guns as well as 2,000 aeroplanes, 500 armoured cars and other equipment such as generating sets, pumping equipment, aeroplane engines, ambulances and lorries. After the war, Austin was busy supplying the growing home market in the twenties and thirties. I write of the motor industry including its war time contribution in How Britain Shaped the Manufacturing World (HBSTMW).

Manufacturing wasn’t only for adults, Chad Valley toys were made in Harborne.

In 1928 chemists at the County Chemical Company came up with Brylcreem and it was an overnight success. So much so that they couldn’t keep up with demand and sold Brylcreem to Beechams.

The Second World War demanded more of Birmingham than even the First. The city became home to shadow factories run by Rover, Austin and Morris, the latter at Castle Bromwich famous for making Spitfires and Lancasters subsequently placed under the management of Vickers. The total production of Supermarine Spitfires was nearly 20,000, built between Supermarine at Southampton and Vickers at Castle Bromwich, which manufactured the largest number, with a small number by Westland. The factory did return to the Morris fold when BMC bought Fisher & Ludlow.

Morris did have their own presence in the city, Morris Commercial Vehicles was registered at Soho; there was also their Wolseley subsidiary, a dedicated tank manufacturing plant and SU carburettors to the south of the city.

Austin at its Longbridge plant manufactured of some 120,000 military vehicles of all kinds ranging from the 8 h.p. utility tourer commonly known as ‘Tillies’, to 3 ton 6×4 trucks, importantly also used as recovery trucks. Also Austin produced a 2 ton truck, of which some 27,800 were built in the war, nearly half being ambulances. In addition, Austin produced 1.3 million rounds of 2, 6 and 7 pounder shells, 3.3 million ammunition boxes, 600,000 Jerricans and 2.5 million steel helmets.

BSA once again rose to the challenge with guns and motor bikes, and Cadbury set up a separate factory making parts for aeroplanes, rockets and respirators. Norton made some 100,000 motor bikes. The University of Birmingham lent its expertise to radar development and the atomic bomb. I write more on motor vehicle manufacturing in the Second World War in War on Wheels.

Dunlop’s contribution to the war effort was prodigious. In his History of Dunlop, James McMillan tells that, ‘between 1939 and 1945 the Company produced the vast majority of the 32.7 million vehicle and 47 million cycle tyres manufactured in the UK’. It was though much more than this, as McMillan goes on to write. Dunlop made 2.5 million disc wheels, 600,000 aircraft wheels, 750,000 tank wheels (plus 1 million tank tyres to go with them), 15 million cycle and motor cycle rims, 3,000 miles of rubber tubing, 600,000 pairs of anti-gas gloves and 6 million pairs of rubber gloves’.

Lucas produced one million sets of starters and ignition sets, a further million and half spare parts sets, but then technical contributions to the jet engine development, electrically controlled aircraft gun turrets, control mechanisms for tanks, wing assemblies for Spitfires and PIAT anti-tank weapons.

In the post war world, Cadbury continued to thrive at Bournville, although now under foreign ownership, and I write of them too in Vehicles to Vaccines. Birds Custard powder was invented by Alfred Bird in Birmingham also in the 1840s. In 1950, it was owned by General Foods of the USA and remained in American ownership until bought by the British Premier Foods in 2004. Kingsmill Bakery part of Associated British Foods are in West Bromwich.

In 1950, Austin manufactured 166,000 vehicles making them second only to Ford at 185,000. One year later they merged with Morris to become the British Motor Corporation.

BMW has manufactured engines since 2000 at their Hams Hill site near Coleshill.

The motor industry has declined but JLR are a continuing presence. Norton Motorcycles once again manufacture in Solihull. I write of the post war motor industry in three chapters of Vehicles to Vaccines: Volume Car Makers, Speciality Car Makers and Commercial Vehicles and Motor Component Manufacturers.The Jewellery Quarter first prospered but then suffered from cheap imports but nonetheless continues and I write of it in the context of designer makers in Vehicles to Vaccines.

So to the early days…..

Introduction

The three elements: industry, growth and environment are intermeshed. Industry will grow not only because of demand for its products but also because of the suitability of the environment and the availability of labour. People will be attracted to a town by the prospect of work and wages; their very presence and the presence of the industry in which they work will impact on the environment. The study thus is one of inter-relationships.

The town selected for investigation is Birmingham because it has grown to become England’s second city having set out very much among the pack of medieval parishes. The story of Birmingham’s industry began in medieval times and its study could quite reasonably go on to the late Victorian era with the coming of such household names as Cadbury and Dunlop, Chamberlain and, a little later, Austin. However the building blocks were firmly in place at the point the town obtained its charter in 1838 and it is at around that point that this review will conclude.

The period of the wars with France from 1793 to 1815 was a watershed for Birmingham in slowing what had been a period of frenetic development. The wars were followed by a period of investigation, which provided a much more detailed picture at a time when the pace had slowed.

The essay will examine a number of different industries and look at population figures and related statistics as well as drawing upon what information is available to paint a picture of the environment. The environment will be addressed in its broadest sense and so not only covering the physical but also the micro environment in which people lived and worked.

Setting the scene

The scene can be well set by a comment from the Tudor period by Leland who visited in about 1538, three centuries before Birmingham was granted the status of a town.

‘There be many smiths in the town, that used to make knives and all mannour of cuttinge tooles, and many lorimers, that makes bittes, and a great many nailors. So that a great part of the towne is maintained by smiths, who have their iron and sea-cole out of Staffordshire.’

It is the latter remark that is key to Birmingham’s story, the availability locally of the raw materials that would build the future of the ‘metal bashing brummy’. Later in the sixteenth century, Camden referred to this by seeing the town as ‘full of inhabitants, and resounding with hammers and anvils, for the most part smiths.’ In 1683 there were said to be 202 forges in the town.

In terms of gaining a picture of the place, Sweet gives an indication of its size in comparison to other places in 1670. Birmingham was said to have population in the region of 6,000, the same as Manchester, a little more than Liverpool or Shrewsbury but less that nearby Worcester.

A little later a comment taken from the foot of Westley’s 1731 plan tells that ‘in the year 1700 Birmingham contained 80 streets, 100 courts and alleys, 2,504 houses, 15,082 inhabitants, once church, dedicated to St Martin, and a chapel to St John and a school founded by Edward the Sixth, and a dissenting meeting house.’

William Hutton, the great Birmingham historian, gave his first impression on seeing the town in 1741

‘I was surprised at the pace, but more so the people. They possessed a vivacity I had never beheld. I had been among dreamers, but now I saw men awake. Their very step along the streets showed alacrity. Every man seemed to know what he was about…’

A description from some fourteen years later adds to the picture:

‘the town, which is another London in miniature: it stands on the Side of a Hill, forming a Half moon; the lower part is filled with the Workshops and Warehouses of the manufacturers, and consists chiefly of old Buildings; the Upper Part of the Town, like St James’s, contains a Number of new, regular streets, and a handsome square, all well-built and well-inhabited…’

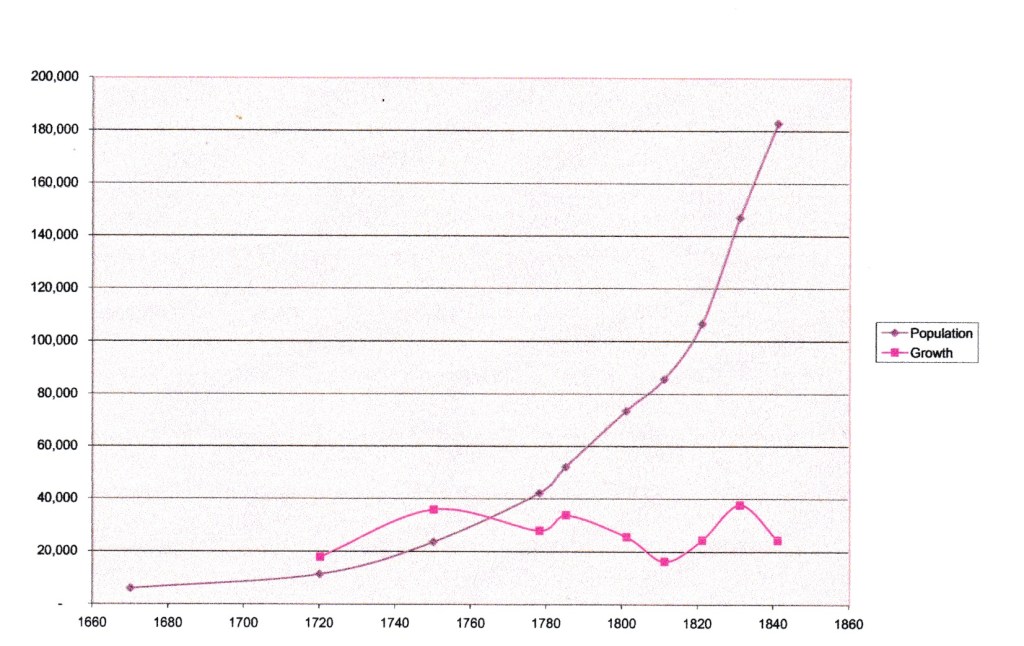

The description of the development of industry and its impact on growth and the environment may be set into context by looking at the population growth over the period under review.

This graph is taken from population figures drawn together by Hopkins. The pink line represents annual percentage growth rates, thus the growth rate from 1670 to 1720 was about 2% per annum. The rate rose in the period to 1750 and then fell, not retaining its former rate until the 1830s.

Industry

Birmingham’s industry began with forges, the working of metal, mainly iron. During the civil war Birmingham had been on the side of Parliament and the output of the forges in the shape of pikes, swords and guns must have been a most welcome contribution. With the Restoration came a new confidence among the ‘middling types’ and a new prosperity. Birmingham was ready and waiting to serve this by supplying not articles of war but trinkets, pins, buttons; those things that were essential to the aspiring family. In doing this, Birmingham had discovered two of the keys to industrialism: the division of labour and the use of small machines. In terms of mechanisation Birmingham was both ahead of its rivals and smaller in the machines it used. In common use by 1750 were the stamp, press, lathe and draw bench. In relation to the division of labour, a pin would undergo some fourteen processes each carried out by a separate worker . The same was the case with the button and the buckle and indeed with all the ‘toys’ which Birmingham produced. The name of John Taylor needs to be mentioned as one of the first in the long line of Birmingham’s entrepreneurs. The skills in toy making were extended into the manufacture of jewellery, the quality of which was said to have improved as the century progressed. The establishment of an Assay Office was authorised in 1773.

Birmingham was a place of small workshops and this is shown clearly in another Birmingham trade of the eighteenth century, gun making. In a way typical, the manufacture of the musket was a process divided up into tens of different parts, up to 63. The manufacture was in a small area of half a dozen streets with small workshops side by side passing parts on for the next process or assembly. There is little evidence of modern ‘clock watching’ work practices with St Monday still observed. Men and women living, working and playing in a tight knit community, the excesses of Sunday being addressed by taking Monday off.

The latter part of the eighteenth century saw the establishment of larger factories alongside the traditional small workshops. It seems extraordinary now that the Soho Manufactory on Handsworth Heath 1765 was regarded as Birmingham’s principal tourist attraction in 18th century. The Soho works was a building drawing on the classic style and dwarfed the traditional small workshop. But itself was really a collection of workshops described as ‘airy and large’, and nothing like the mills of further north, The advent of Watt’s steam engine manufactured at the Soho works was perhaps ironic for Birmingham given the very small extent to which it was actually employed in the town. In the gun making business, for example, only barrels benefited from steam power in rollers, the remainder being manual. Other major employers included Turner & Sons (buttons) employing 500 people , James James (screws) employing 360 people mainly women, and the Islington glass works with 540 employees.

Another major trade was brass. Made from copper and calamine, imported respectively from Cheshire and Bristol, Birmingham worked in brass by initially by casting but after 1769 by stamp and die. As demand grew, the brass itself was made in Birmingham, for example by the Birmingham Metal Company off Broad Street in 1781. In 1790 the brass manufacturers combined to found their own companies to produce copper in Redruth and Swansea. The number of works increased from 50 in 1800 to 280 in 1830 and 421 in 1865. Size also increased and this shift from the small workshop enabled both efficiency and more control. It also won its plaudits: ‘What Manchester is to cotton, Bradford in wool, and Sheffield in steel, Birmingham is in brass.’ W.C. Atkin. Birmingham minted coins and other brass fittings were used world wide.

Technology did not impact on Birmingham in any headline breaking way, save for the steam engine and, as we have already seen, its impact on Birmingham manufacturing was not great. Technology did however have a positive effect on the suppliers of raw material, the Black Country Iron industry and in many small ways in Birmingham itself based on the evidence of the number of patents granted. Prosser observed that ‘Birmingham stood first among provincial towns as regards the numbers of grants of letters patent.’ The web site Virtualbrum tells more: ‘Henry Clay, one of John Baskerville’s apprentices, patented papier-mache in 1772, while two brothers named Wyatt patented a machine for cutting screws— work which had hitherto been done by hand. Another townsman, named Harrison, made a steel pen for Dr. Priestley. Josiah Mason later started one of the largest factories in the world for the manufacture of pens.’ A pointer to Birmingham’s intellectual future was the Baskerville’s press, whose first project was Virgil printed in 1757.

Bisset draws a neat picture in his 1800 Magnificent Directory:

Inventions curious, various kinds of toys,

Engage the time of women, men, and boys,

And Royal patents here are found in scores

For articles minute – or pond’rous ores.

Birmingham manufactured goods were being used in Europe and America and in farther flung places with a good proportion of its production going overseas . With this international flavour and more particularly with the gun trade, it was inevitable that the wars with France would be a significant driver. The French wars between 1793 and 1815 set a solid demand for guns, which, when added to for demand for sport and in slave trade, meant strong demand in this sector which only declined after the peace. War did however decimate the other industries . The decades either side of the end of the century were not ones of great prosperity. They were however years when Birmingham’s tradition of self help came to the fore with skilled workers robbed of work able to a degree to fall back on the Friendly Societies which they had formed. The period after the wars saw a faltering return to prosperity which did not really get under way until the 1830s.

Daily life

It is possible to gain a view of Birmingham’s environment which is of unremitting grime and industry. William Toldervy visiting the town in 1762 gave another slant:

‘I entered the town on the side where stands St Philip’s…This is a very beautiful modern building… There are but few in London so elegant. It stands in the middle of a large Church yard around which is a beautiful walk…on one side of the Church-Yard the buildings are as lofty, elegant, and uniform as those of Bedford Row, and are inhabited by people of fortune.’

A good number of these people of fortune were unlikely to have attended St Philips, their preference being for non-conformist forms of worship. Hutton had ascribed to the growth of Birmingham the reason that its lack of a Charter gave freedom to dissenters to set up and trade. There is much evidence that they did, given the number of dissenter meeting houses as well as a Roman Catholic Church and Jewish Synagogue. The dissent tradition also lead to a growth in radical politics.

The industry of Birmingham sucked in people and those people needed places to live. Birmingham was blessed with ample available land and so the overcrowding known in other urban centres was far less prevalent in Birmingham. The first phase of building took place in central areas, with the once better houses broken up into multiple dwellings and with workshops built where before there had been orchards. Further new building took place on the outside of the town in the direction of the neighbouring parish of Deritend. Later building would enlarge the town to the north and north west. The common design for working class habitation was the court , with earlier examples extremely cramped. There were also back to back streets as found elsewhere in England.

Hutton was impressed by the rate of house building in the latter half of the eighteenth century, which he described as second only to London. He says ‘from 1741 to the year 1781, Birmingham seems to have acquired the amazing augmentation of 71 streets, 4,172 houses, and 25,032 inhabitants.’ The picture is thus of a busy town, with people applying their skills and making money. Small workshops meant a close environment. The sheer number of people though meant noise and bustle. Also a huge amount of waste material causing streets to be unpleasant places particularly in warmer weather. This was addressed in 1769 by ‘A Bill for Laying Open and Widening certain ways and passages within the Town of Birmingham; for cleansing and Lighting the Streets, Lanes, Ways and Passages…’ It’s success seems limited with reports of open sewers even on the middle class Edgbaston .

The Granger report paints a varied picture of the work environment from speaking of the sanitary conditions at work in Phippson’s Pin Manufactory, where 100 girls and boys had between them only one privy, to James James’ screw manufactory described as an ‘admirably conducted establishment in all its branches.’ These comments relate to the larger factories. But as is clear from Granger and as Samuel Timmins pointed out in 1866 this was far from the end of the small enterprise:

‘Beginning as a small master, often working in his own house with his wife and children to help him, the Birmingham workman has become a master, his trade extended, his buildings have increased. He had used his house as a workshop, has annexed another, has built upon the garden or the yard, and consequently a large number of the manufactories are most irregular in style’

The physical state of many small workshops was grim. Granger described many as being ‘old and dilapidated’. Many were housed in garrets and were cold, damp and dirty. The close environment though engendered a sense of community which was less prevalent in larger establishments. The labour of children and women was common . The role of children was to support the main adult worker, often a parent. The significant presence of married women in the workplace is blamed for the relatively high infant mortality rate in a town considered healthier than many of its contemporaries.

The growth in industry also impacted on the wider environment. Demand for Birmingham’s goods needed increasing quantities of raw material. Also the finished goods too were of little use if left in Birmingham; they had to reach their market. The problem of raw materials was addressed by the building of a network of canals. WT Jackman in his Development of Transportation in Modern England observed that ‘Birmingham was becoming the Kremlin from which canals radiated in all directions.’ The problem of finished goods was addressed by an increase in the number of Turnpikes but was not solved until the coming of the railways, which it seems were well suited to serve the broad based Birmingham economy.

The year 1840 saw the publication of the Chadwick report which gives an objective and comparative view of Birmingham ranked against other English cities:

‘The great town of Birmingham…appears to form rather a favourable contrast, in several particulars, with the state of other large towns…the general customs of each family living in a separate dwelling is conducive to comfort and cleanliness, and the good site of the town, and the dry and absorbive nature of the soil, are very great natural advantages.’

Chadwick also noted that ‘the principal streets were well drained, there was a plentiful supply of water and there were no cellar occupations, fever was not prevalent and some allotment gardens remained’ To set against this, an observation was made on the physical condition of Birmingham’s men in the context of army recruitment. ‘The general height of men in this town was 5’ 4” to 5’ 5”, many are rejected because of narrow chest and want for stamina.’

Another view of English cities was written by Friedrich Engels. In his 1845 book The Condition of the Working Class in England, Birmingham does not feature to any great extent. However he does quote a particularly scathing passage on Birmingham’s courts: ‘…in the older parts of the town there are many inferior streets and courts, which are dirty and neglected, filled with stagnant water and heaps of refuse.’

The quotation goes on to draw attention to the narrowness and poor ventilation. The editor in his footnote makes a telling point by adding the start of the quotation which Engels omitted:

‘Birmingham, the great seat of the toy and trinket trade, and competing with Sheffield in the hardware manufacture, is furnished by its position on a slope falling towards the Rea, with a very good natural drainage, which is promoted by the porous nature of the sand and gravel, of which, the adjacent high ground is mainly composed. The principal streets, therefore, are well drained by covered sewers’.

We should probably resist any temptation to imagine life in the courts and back to backs in Birmingham as in any way comfortable. Nevertheless there is no reason why we should not infer a sense of community or communities amongst its inhabitants: the role of the pawnbroker and publican, the significant role of women in holding family and community together. In terms of recreation, the chief place was the Vauxhall Gardens, described as ‘ place of quiet way from the noise and smoke, but also the venues of extravagant public celebration and fireworks.’ For indoor entertainment there was the Appollo Hotel on the towns outskirts opened in 1787, ‘peculiarly adapted to Public and Musical Entertainment’ and pubs a plenty.

Some evidence of the inevitable unpleasant environment created by so much smoke and decaying waste is available from the march of the middle class into nearby Edgebaston and the consequent running down of central areas for example that surrounding St Philips previously so highly regarded. As a suburb Edgebaston may strike us now as remarkable with some houses with ten acre gardens. The suburb provided the environment for the dependants of businessmen. For the men there were meeting places for example, Freeth’s Leicester Arms (or coffee House) in Bell St, Joe Lindon’s Minerva Tavern in Peck Lane. Also two freemason lodges.

We can though see Birmingham as a far more integrated social environment than some other cities. Against the backdrop of stark economic conditions, the creation in 1830 of the Birmingham Political Union brought together middle classes and the skilled working classes to press Birmingham’s case.

The enduring picture must be of a city abounding in enterprise and civic pride.

The 1851 census provided a detailed breakdown of the population by occupation and so provides a means by which to take stock:

| Blacksmiths | 1,091 | Iron manufacture | 2,015 |

| Brassfounders | 4,914 | Other workers and dealers in iron and steel | 3,864 |

| Bricklayers | 1,694 | Labourers | 3,909 |

| Button-makers | 4,940 | Painters, plumbers, glaziers | 1,097 |

| Carpenters, joiners | 1,851 | Messengers, porters | 2,283 |

| Cabinet-makers | 1,027 | Milliners | 3,597 |

| Cooks, housemaids, nurses | 1,113 | Shoemakers | 3,153 |

| Domestic servants (general) | 8,359 | Tailors | 2,009 |

| Glass manufacturers | 1,117 | Tool-makers | 1,011 |

| Goldsmiths, silversmiths | 2,494 | Washerwomen | 1,965 |

| Other workers in gold and silver | 1,153 | Workers in mixed metals | 3,778 |

| Gunsmiths | 2,867 |

Birmingham had increased in size over two centuries some thirty fold. There were still blacksmiths as there had been quite possibly at the time of Roman occupation. The manufacturing industries were there en masse but they had gathered to them the whole infrastructure of the great Victorian town. Houses needed to be built and maintained and so the building trades were well represented. The middle classes needed serving. The largest section of the working population did just this, together with the providers of related services. But all these people were certainly part of the demand for the manufactured goods and so the circle turns.

The abiding impression from this survey surely must be the ingenuity of the Birmingham people. This is not the story of cotton mills and giant machines but of the steady clever graft of thousands of people. The picture is nonetheless mixed with some dreadful living and working conditions sitting cheek by jowl with fine buildings, gracious living and state of the art manufacturing.

The authors who have studied the growth of Birmingham have struggled to pin point single reasons for the development of its industry. It does however seem to centre on the broad base of skills and the availability of raw materials and the space in which to grow. Nevertheless, there seems to be an enduring metaphor in the realisation that the foundation of England’s second city was built on the whim of fashion. Matthew Boulton, one of the greatest of Birmingham businessmen was to reflect near to his death in 1809 that ‘Birmingham was as remarkable for good forgers and filers as for their bad taste in all their works.’ He went on to refer to their past-times ‘their diversions were bull-bating, cock-fighting, boxing matches, and abominable drunkenness with all its train.’ But then to the improvement he had witnessed over his lifetime, ‘But now the scene is changed. The people are more polite and civilised, and the taste of their manufactures greatly improved.’ The baton carried by Boulton, Taylor and others was passed to Chamberlain in what had good reason to become England’s second city.

I am grateful to Russell Arthurton for his research in Percy Mills of WT Avery.

Further reading

Birmingham – The Workshop of the World, Carl Chin and Malcolm Dick eds. (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2016)

Chadwick, Sanitary Inquiry – England No 12 Report of the State of the Public Health in the Borough of Birmingham Local Reports on the Sanitary Condition of the labouring population of England (HMSO 1842)

Dent, Robert K The Making of Birmingham (Birmingham: Allday; London: Simkin, Marshall and Co, 1894)

Granger, Children’s Employment Commission, Appendix to the second report of the Commissioners Trades and Manufacturers Part 1 Reports and Evidence of the Sub-Commissioners (Shannon: Irish University Press)

Henderson, W.O. and W.H. Chaloner trans Engels The Condition of the Working Class in England (Oxford: Blackwell 1958)

Hopkins, Eric The Rise of the Manufacturing Town Birmingham and the Industrial Revolution (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1989; Stroud: Sutton, 1998)

Kellett, John R. The Impact of Railways on Victorian Cities, (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1969) p.148.

Sweet, R., The English Town 1680-1840: Government, Society and Culture (London, 1999)

Thompson, F.M.L. The Rise of Respectable Society, A Social History of Victorian Britain, 1830-1900 The Fontana Social History of Britain since 1700 General Editor F.M.L. Thompson (London: Fontana 1988)

Tyzack, Geoffrey The Civic Buildings of Birmingham, The English Urban Landscape Philip Waller Ed. (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press 2000)

Upton, Chris, A History of Birmingham (Chichester, Phillimore 1993) p.68

Wise M.J. On the Evolution of the Jewellery and Gun Quarters in Birmingham

You can read more in my books How Britain Shaped the Manufacturing World and Vehicles to Vaccines

Good article here. Thank you. Reading up quite a bit here as I’m a video producer that specialises in manufacturing and industrial sectors.

LikeLike