‘Doing well’, how can this be judged? Is it a measure of well being? If it is, is there enough oral history to provide evidence of it, since, by and large we tend to comment on the shortcomings of life and not its fullness? If it is to be assessed, is it to be done with the parameters of the twenty-first century writer? Or do we seek to compare but do so in its historical context? St Albans did well when compared to Jarrow; the comparison of unemployment shouts from the roof -tops. Yet in her book, The Story of St Albans, Elsie Toms tells that ‘the poorer parts of the towns were dire slums, a disgrace to any decent community.’ But this is perhaps an extreme example; the comparative of doing well gravitates to the middle ground where Stoke might be compared to Leicester. Stoke is praised by J.B. Priestley on his English Journey for the seeming satisfaction of its workforce . Leicester receives universal acclaim courtesy of the Statistics Bureau of the League of Nations .

Even if such data were readily available, the task of assessing which urban areas were well doing by means of oral history or contemporary commentary might fail to provide an objective assessment. A more consistent measure is needed. Were this essay covering the last thirty years, statistics abound for the assessment of comparative prosperity. However, in the period under review, the absence of readily available detailed regional GDP data meant that another measure was needed. This would identify broad areas of light which could then be investigated in more detail.

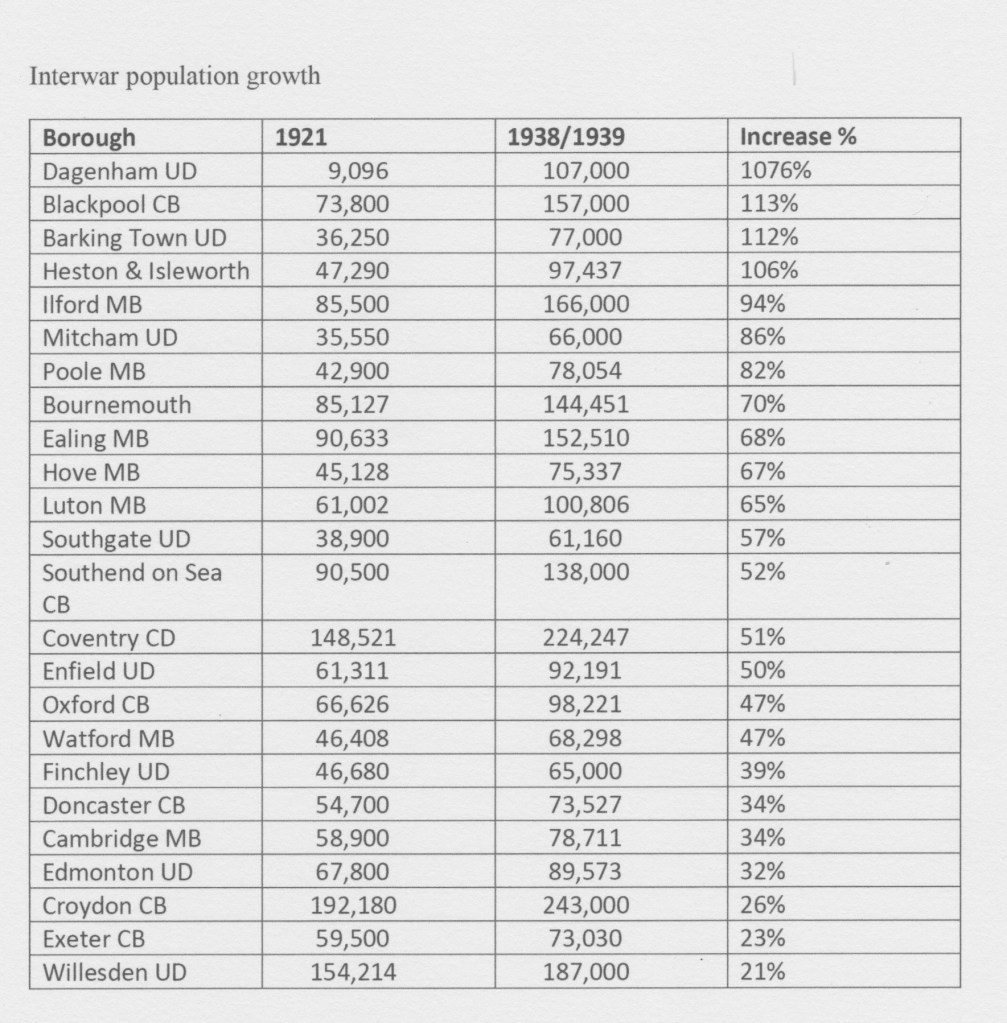

The indicative data selected was population growth from comparing the 1921 census to the figures for 1931, 1938/1939. From these a number of high rates stood out. The location of these places was considered and a number of themes emerged which were then followed by more detailed investigation. At the same time the overall economic picture was considered alongside regional unemployment rates. JB Priestley’s English Journey was an invaluable source of human observation which added to the overall picture.

In their book on the Economy of Inter-war Britain , Sean Glynn and John Oxborrow begin by acknowledging a paradox. The inter-war years were a period of good growth but also a time that saw high unemployment and distress in a significant part of the population. They do however say that ‘the growth which occurred benefited a large proportion of the population. But how did this look? In the introduction to his book British Society 1914-45, John Stevenson paints the picture of society in 1950 as imagined by a visionary in 1900. The picture is of change. The replacement of what was bad with what was good: improvements in lives, economic prosperity, opportunity for all. The visionary could never have predicted the horrific affect of two world wars, nor perhaps the depression. Nevertheless the comparison of 1950s Britain with the imagined picture is remarkable. Much progress had been made.

The concern of this essay though is with the inter-war years. In looking at the economy Stevenson points toward the new industries as those places which were doing well and were producing the overall economic growth. He looks too at the massive growth in housing. But there was much else, swathes of those places that had done well in the past but did so no longer. Priestley spent much of his journey in such places. We are perhaps therefore looking in a period of grey for patches of light.

Two essays add complexity to the picture. The first written in 1967 by John Aldcroft highlights the new industries as the cause of the overall economic growth. The second written by Patrick O’Brien in 1987 questions this, pointing more to the economy as a whole with the exception of the older industries and with the emphasis on housing.

It can been seen from the table that those places of the highest growth were very nearly all what we know now as the London suburbs. A.J.P. Taylor with his broader brush on a longer time frame encapsulates what had happened ‘All England became suburban…Middlesex, Kent, Essex and Surrey doubled in population between 1911 and 1951. Robert Bruegmann makes the astonishing point that whilst London’s population increased by 10% it doubled in land area.

Other places also attract attention: Poole and Bournemouth, Southend on Sea, Hove and Blackpool; Luton, Coventry and Oxford. Certainly some case of the growth will be the result of changes in boundaries. Exeter and Doncaster are perhaps examples of these.

Looking more specifically at the second decade of the inter war years other names appear: Slough and Bedford, but again the overwhelming majority come from what we know now as greater London .

Before looking more closely at the urban areas, there are further broad statistics which help to paint the picture. The period between the wars was, as already noted, one of overall economic growth, but uneven and marred by high unemployment.

The upper line represents GDP per head of population. The lower the percentage of unemployment.

Stevenson provides regional statistics on unemployment for 1929, 1932 and 1937 which show that unemployment was lowest in the South East and the Midlands. However, all areas suffered severe increases in 1932 as a result of the great depression. Glynn provides figures for industrial output per industry sector comparing 1924 with 1936. The industries that were doing well were engineering, utilities and food drink and tobacco; but also iron and steel, paper printing and stationery, chemicals, building and building materials and clothing. These two pieces of data can be seen in GDP terms but over a longer period in Nicholas Crafts’ paper Regional GDP in Britain, although focusing on the period up to 1911, does offer statistics for the percentage growth between 1911 and 1954. These confirm that the fastest rate of growth was in the South East, but followed by the West and East Midlands. A further look at the census confirms that Birmingham was huge and growing, having reached a population of 1 million by the outbreak of the Second World War.

The most significant development was housing and the way London spread out between the wars like an inkblot on the map of England. John Betjeman captures what has happened in his poem Middlesex, from which the following lines are taken:

Recollect the elm-tress misty

And the footpaths climbing twisty

Under cedar-shaded palings,

Low laburnum-leaned-on railings,

Out of Northolt on and upward to the heights of Harrow Hill.

In his book Semi-detached London , Alan Jackson tells of the phenomenal growth of London. He points first to the initiatives of government. The whole housing issue was vastly broader than just London. Lloyd George’s words were addressed to the nation: ‘What is our task? To make Britain a fit country for heroes to live in.’ Wolverhampton November 1918. Richard Roger in his essay Slums and Suburbs tells of the pressures that had grown before the outbreak of war as a result of the rate of house building slowing. He adds that in the war years building had almost ceased. In the short-lived post war boom the first of three major building phases got under way with large scale building by local authorities, the Addison programme, This was followed by a longer period of less generous general needs subsidies under Chamberlain and Wheatley. Finally in the run up to the Second World War, government focused on slum clearance. In the inter-war period over a million houses were built by local authorities. This paled into almost into insignificance when compared to the near three million built by often speculative private enterprise.

Jackson emphasises the significance of private enterprise in Greater London Area where the annual private enterprise housing build rose from 34,000 in 1929 to 45,000 in 1931, in 1934 73,000 . He cites the reasons for the growth as being the low cost of materials and the availability of cheap money. Suburbia became essentially a mass of housing built up around railway stations with little industry or other social infrastructure. John Betjeman from the same poem gives one of the clues: ‘Gaily into Ruislip Gardens – Runs the red electric train.’ Without the expansion of the railways and the underground in the pre-war years none of the suburban sprawl would have been possible. Looking more closely at particular areas, in his book on Southgate and Edmonton, Graham Dalling highlights the extension as the Piccadilly Line as ‘unleashing a building boom’. The picture is of a clerk working in the City taking the train to his home in Essex, or of one employed in the West End taking the train at Charing Cross into Kent or Victoria into Surrey.

The mention of clerks picks out some of the brighter burning lights. The inter-war years were those when the middle classes came further into their own. The increase in the production of paper printing and stationery may bring a wry smile but it is evidence of the growth in the numbers of Englishmen, and indeed women, who pushed pens rather than ploughs. Glynn tells that ‘the number of salary earners increased from 8.3% of the occupied population in 1911 to 13.8% in 1931 and 14.3% in 1938’. Jackson paints the picture of the lives of these people. Estates of new houses, frequently draughty, certainly initially isolated often in the sea of mud of a building site. Middle class life became privatised as the home became the focus, often demanding such a position by the ever hungry mortgage and need to keep up with the Jones’, a phase and way of life inherited from the USA. In time the USA and Hollywood though provided the pleasure that stamped the imprint of ‘doing well’ on the London suburbs, with Oscar Deutsch’s promise to ‘ring London with Odeons.’ This was the time of the Lyons Corner House and in the home the Ecko Superhet radio. Back in 1924 Wembley had been chosen for the British Empire Exhibition. Anne Clendinning writing about the gas industry talks about it seeking to appeal to a wide spectrum of women and bring design and flair into the home. Many middle class households had domestic servants. Stevenson tells of Marks and Spencer opening 129 stores across England between 1931 and 1935. Liptons, Sainsbury and Woolworth were also household names by time war broke out once more. These were urban areas doing well, at least once the community infrastructure was in place.

The lot of the working class in greater London between the wars may not have been quite so bright but was significantly better than for their northern brothers. Andrzej Olechnowicz tells of local authority housing and the initiatives by the LCC. The intention was to create communities with low density of housing. However the time estates took to complete made this either illusionary or unachievable. Nevertheless objective judgement would point to life on the estate being better than that in the slums they were built to replace. Jackson tells how industrial development appeared on the site of war factories in the west and north west. There was also development along the rail routes to Bristol and Birmingham, out to West Hendon, Croydon and the Lea Valley and along the 210 miles of new roads built in the 1920s. Factories employing 25 or more increased by 532 in Greater London in 1932-37. 97,700 jobs, or 2/5 of all employment created by 664 new factories in Britain during the period. On the start of his English Journey, J.B.Priestley witnesses the western exit from London and he observes the new style of factory, the new names that were to be become the familiar entry into the metropolis for the middle twentieth century generations.

Housing aside, the question still falls to be addressed: why did it happen there? Glynn argues that the South East and also the Midlands were ready and waiting for the post war development of new industries . They had traditionally mixed economies with the corresponding breadth of skills. They also already had population and the new industries were very much geared to the consumer and the domestic market. The1928 Liberal Party paper Britain’s Industrial Future supports this. The new industries were freer than hitherto over their ability to choose location. The single most significant factor that provided this freedom was the shift in the source of industrial power from coal to electricity . Glynn tells how the Central Electricity Board was established 1926 and how the number of customers increased from 0.7 m in 1920 to 2.8 m in 1929 and 9m in 1938. The amount of electricity generated quadrupled between 1925 and 1939. The electrical engineering workforce doubled between 1924 and 1937 to 367,000. The creation of the national grid mainly between 1929-1933 was also fortuitous in providing employment and demand for steel and aluminium in the depression years.

Another driver for the location of new industries was that stemming from the barriers to international trade. The liberal hegemony in Britain was intermeshed with the doctrine of free trade. The market would decide. The result was the collapse of exports in the old industries. In the late twenties there was a growing political will to put up tariff barriers to protect what industry was left. One side effect of this was the encouragement of foreign owned businesses to set up manufacturing in Britain. The still vivid example of this is Hoover at Perivale in Western London where its great art deco factory remains albeit in a different use.

Still in the South East but turning away from industry to the fruits of industry, Priestley headed south on his journey. This essay can pick up both on Southampton where he went but also the southern coastal towns identified for their growth in population. Southampton was perhaps a microcosm of England doing well, in parts. Priestly heads for the port where the great liners docked. The scene hints of glamour. He turns though to the side streets which hint rather more strongly of poverty. Southampton provides a connection back to middle class London, upper middle class London. Looking to one of the great authors of the inter war period Arnold Bennett, in his novel Imperial Palace, he paints the picture of people doing well, in that instance having docked at Southampton from New York. The author observes that the well being of the Atlantic trade was vital to the well being of the great London hotels. A number of these were fine art deco products of the inter – war period.

In her paper London by the Sea , Sue Farrant tells that the south coast resorts had mostly been through their hay day in the 1880s. However, following the Armistice, Brighton, in particular, became aware of its overcrowded and run down appearance. The housing boom of the inter-war years combined with the improvements to railways from London led to a massive redevelopment not only of Brighton but other south cost towns. Brighton’s population hardly altered but its combined rateable value increased by half a million. The extent of development prompted Country Life to comment ‘What we would not give to be able to put the clock back, say, twenty years to remove all the bungalow towns from our coasts and start again…Peacehaven came in to being through carelessness and lack of forethought.’ What is doing well for some people is perhaps the opposite for others. The south coast at that time is still recalled as a recent article in the Guardian tells. ‘St Leonards for example saw an ‘epic seaside complex, which once included an Olympic pool with tiered seating for 2,500 spectators. Another the De La Warr pavilion at Bexhill-on-Sea was described as a modernist masterpiece.’ Bournemouth and Blackpool benefited too from the increased interested in the seaside.

If the South East was growing fastest, the South Midlands with its embryonic motor industry was only a little way behind. The question of whether the urban areas in which it was located were doing well is more complex. Two books tell essentially the same story but in different places and from different stand points. Thomas and Donnelly writing of Coventry’s Industrial economy and Lynam writing on Domestic life in Coventry tell an up beat story of the city they saw as the heart of the motor industry in Britain. In contrast R.C. Whiting in the View from Cowley dwells rather more on the difficulties principally in labour relations. Graham Turner in The Car Makers offers perhaps a more balanced account. The motor industry was complex. The product was price sensitive and had to be produced in volume to be commercially viable. The industry and thus those who worked in it were under pressure. For example the practice in the industry was to lay off workers in the summer as new models were prepared for the autumn’s motor show.

If it can be said that those towns in which the motor industry was growing were doing well, where were they? In Coventry there was Rootes, Standard and Jaguar and in Oxford Morris. But the industry extended wider with Vauxhall in Luton and Bedford in Bedford, with of course Ford in Dagenham having re-located from Manchester. It was not only the assembly factories, the industry was characterised by a complex network of component manufacturers, where there is surely an echo of Birmingham from its early days and indeed in Birmingham there was Lucas making lights and Dunlop tyres, as well as Austin making cars. In London there was Smiths and their instrumentation business, among others.

Stevenson talks more generally about the ‘new industries’. He tells how new practices had been introduced: statistics and accounting systems and management. He highlights engineering generally and tells how by 1937 production was some 60% higher than in 1924. This included motor vehicles but also aircraft, cycles, electrical equipment and consumer durables. In her essay on regional development Carol Heim points to the west London area as being key to manufacturing for the consumer market, boasting many household names. She highlights the relatively small size of many enterprises in the 1920’s. Both she and Stevenson see the picture changing in the thirties with a rationalisation of smaller units in to giant combines: ICI, EMI, Unilever, Courtaulds, Royal Dutch Shell, Nestle and Dunlop. Plastics and artificial fibres were important. Bakelite probably featured in most homes by the time of the war. In telling the history of Courtaulds, C.H. Ward-Jackson captures an aspect of the spirit of doing well in the twenties. ‘with the early twenties arrived the bobbed hair flapper on the pillion of a motor cycle – cosmetics that were respectable – the night club. The sensuous saxophone usurped the romantic violin. The Bright young things were ‘the latest’ . They were wearing rayon the golden egg of Courtaulds. Elsewhere ICI was founded in 1926 and Stevenson tells of 100,000 employed in the chemical industry by 1939. EMI employed 15,000 in Hayes in West London. Kodak with the ‘box brownie’ established in Harrow and Hemel Hampstead. Stevenson adds that new industries accounted for 1/5 of national output by 1935.

Mention has already been made of Leicester, although it didn’t feature in the list of major population growth, it gives a clue to sustained urban development and ‘doing well’. Rodger explains that Leicester’s built environment took on a major burst of growth in the late 19th century with a very positive effect in terms of the quality of building. Reeder points to Leicester’s comparative economic position in the inter-war years when it was regarded as the second most prosperous city in Europe. In trying to reach the reason for this he points to its prominence in footwear and woven textiles, but also the broad base of skills which were employed in engineering and electronics.

In drawing the strands together, Stevenson’s image of the visionary is helpful. What actually had happened in the space of twenty years? Housing had spread hugely. This surely would be impossible to miss. Working class occupants would enjoy the physical standards but may still miss the tight knit community of the slum. Middle classes hid behind their suburban curtains but could escape into flights of fantasy in the cinema and huddle round the radio. The upper middle and upper classes always do well, although individuals moved in and out as circumstances change. On the industrial scene by the end of the period new Industries accounted for 1/5 of national output. The physical look of the country had changed as Stephen Spender in his poem ‘The Pylons’ illustrates. ‘Pylons, those pillars | Bare like nude, giant girls that have no secret.’

The picture to emerge though is one more of change than Elysium. The huge amount of re-housing was seriously overdue and even by the time the Second World War broke out, many slums still remained. The amount of work that fell to be done in the fifties is evidence of this. But it must have felt better. If the economy wasn’t a success story, it could have been vastly worse. In terms of the new industries it was perhaps more a period of preparation for the comparatively better times that were to come, again in the fifties. The fact that the new industries were concentrated in the South East and Midlands must have meant that those urban areas were doing well if only in comparative terms.

The period was a traumatic time for government: the vast problem of housing with no money to address it properly and quickly; the ball and chain of the gold standard preventing spending and killing exports; the deep wound of the national strike and then the great depression. The period of comparative prosperity must have been a blessed release. It is perhaps no wonder that Prime Minister Baldwin was so reluctant to let it go.

Which urban areas did well? The essay set out to identify patches of light on a grey landscape. The picture, which has emerged, is much more a background of shades of grey, some quite light, but with ugly smudges of black.

In order to write this essay, I drew on the following sources:

Aldcroft, Derek H., Economic Growth in the Inter-war Years: A Reassessment, (The Economic Review, New Series, Vol.20, No. 2 (Aug., 1967)), 311-326

Betjeman, John, Collected Poems, Lord Birkenhead ed (London; John Murray, 1958, fourth edition 1979)

Clendinning, Anne, Demons of Domesticity Women and the English Gas Industry 1889-1939,(Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004)

Crafts, Nicholas F.R. Regional GDP in Britain, 1871-1911: some Estimates (Department of Economic History London School of Economics 2004)

Dalling, Graham, Southgate and Edmonton Past (London: Historical Publications, 1996)

Farrant, Sue London by the Sea, Resort development on the south coast of England 1880-1939

General Census report 1931.

Glynn, Sean and Oxborrow, John, Interwar Britain, A Social and Economic History (London: George Allen & Unwin 1976)

Hannah, Leslie, Electricity before Nationalisation (London and Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1979)

Heim, Carol E., Industrial Organisation and Regional Development in inter-war Britain, (The Journal of Economic History, Vol.43 No.4 (Dec. 1983)), 931-952

Jackson, Alan, A. Semi-detached London, Suburban Development, Life and Transport, 1900-39 (London: George Allen & Unwin 1973)

Lancaster, Bill and Mason, Tony eds. Life and Labour in a 20th Century City (Coventry: Cryfield Press)

O’Brien, Patrick K. Britain’s Economy between the Wars: A Survey of a Counter-revolution in Economic History (Past and Present, No. 115 (May, 1987), 107-130

Olechnowicz, Andrzej, The Council Estate Community, in The English Urban Landscape Philip Waller ed (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2000)

Priestley, J.B., English Journey (London: Heinemann 1934; London: Penguin, 1977)

Reeder, David, The Local Economy in, Leicester in the Twentieth Century, David Nash and David Reeder eds (Stroud: Alan Sutton, 1993)

Rodger, Richard, The Built Environment in, Leicester in the Twentieth Century, David Nash and David Reeder eds (Stroud: Alan Sutton, 1993)

Rodger, Richard, Slums and Suburbs, in The English urban Landscape Philip Waller ed (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2000)

Taylor, A.J.P., English History 1914-1945, The Oxford History of England (Oxford; Oxford University Press, 1965)

Toms, Elsie, The Story of St Albans (St Albans: Abbey Mill Press, 1962)

Turner, Graham, The Car Makers, (London: Eyre & Spottiswood, 1963)

Ward-Jackson, C.H. A History of Courtaulds (For private circulation 1941)

Watson Smith, S. ed, The Book of Bournmouth (Written for the British Medical Association meeting 1934)

Whiting, R.C. The View from Cowley: The Impact of Industrialisation upon Oxford, 1918-1939, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1983)

http://wwwuk.kodak.com/UK/en/corp/kodakInUK.jhtml?pq-path=2218 accessed 5/12/05